Because of this, serifs are still generally the go-to typeface for printed works such as books or reports, though it’s not an absolute rule. Essentially, serifs allow for more comfortable reading at length, as the serifs guide the eye smoothly from character to character, making the serif ideal for long-form printed works. Generally, serifs have a longer history than san serifs, as they were the first typefaces used to print books following the invention of the Gutenberg Press.

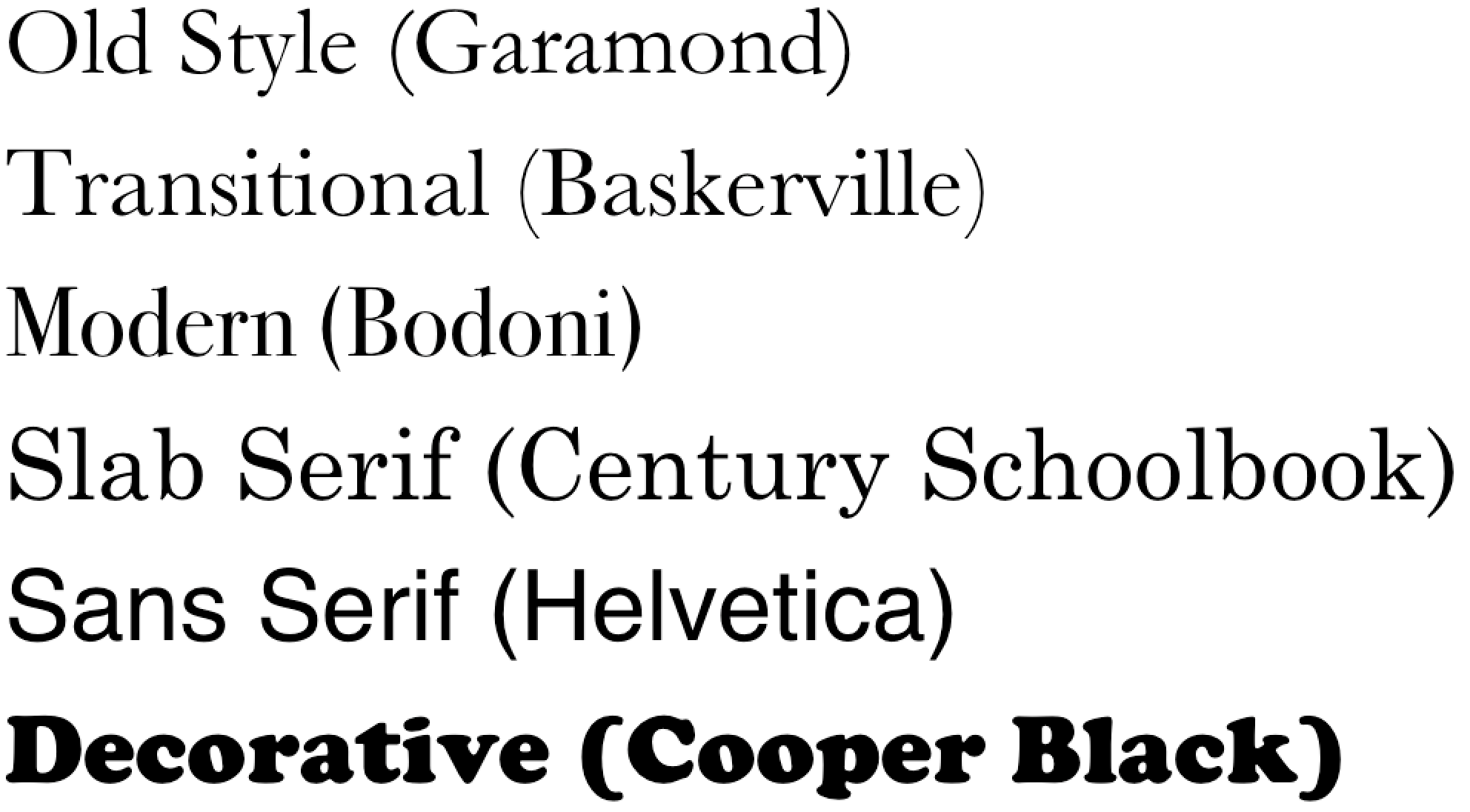

Even some of the fonts originally designed for screens have become outdated as displays and printers become higher resolution and capable of displaying more complex shapes accurately. Thus, there have been many alternatives or updates created since they were introduced. Each of the typefaces in this article is decades, if not centuries old, and were all designed for different technological contexts. Some of the most influential typefaces in use today are often overlooked in favor of unique typeface designs that are newer to the market-and sometimes rightly so. Do most designers even know about the original industrial contexts for which various typefaces were designed? What do these contexts and histories mean for determining the legibility, appropriate character, and use of a given typeface? No matter what design discipline one is working in-whether it’s visual design or UX or traditional print design, typefaces are essential elements of virtually every bit of design produced. But how many people ever really notice the typeface styles they’re surrounded by every day?Įven designers underappreciate typefaces and often form type decisions on loosely-based opinion rather than objective understanding.

From the apps on their phones to the grooming products in their bathrooms to the signs they see on their morning commute, typography is everywhere. The vast majority of people are bombarded with typefaces from the moment they wake up in the morning until the moment they go to bed at night.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)